It’s two months until Arran Open Studio’s 2023! In this month’s tour of participating studios, writer Emily Rose Mawson discovers David Bowie in glass, chairs made from Lochranza whisky barrels, and intricate cut paper designs of Arran wildlife.

GLASS

Paul outside his studio

In a garden behind the main street of Lamlash sits a shed of invention, a Wonka-style laboratory of coloured powders and Volcano-hot (almost) kilns. Beside a rainbow of exquisitely detailed glasswork – Buddhas, Celtic crosses, diving dolphins and famous faces on chequered screens – there are trays of scrabble-sized pieces of glass. “These are what I use to make David Bowie,” says fused glass artist Paul McGarrie, tinkling one of the trays. “It’s something about Bowie’s bright amber eye – it really comes out in glass work.” And the Bowie glassworks sell as quickly as the Arran Open Studios participant can take them out of the kiln. The same can be said for most of Paul’s creations, though: as soon as an idea pops into his head, he designs it, makes it, and it sells, often the very same day.

On the day I visit his studio, which also features on the Arran Art Trail, he’s experimenting with a topographical map of the Isle of Arran – its mountains and valleys replicated in glass the colour of the ocean and shimmering in a container of water. The model was inspired by a video Paul watched of a designer 3D-printing New York City from Google Maps. “That’s what I want,” he said to himself, and he worked out how to transpose the technique to Arran.

This is what’s remarkable: Paul is entirely self-taught. I wonder where you begin with shaping glass. “Video tutorials,” is his simple response. Paul attended art school in the 1990s but didn’t enjoy it – “it taught me that I didn’t want to paint”. When he left, he had various jobs, but the turning point came 10 years ago when he decided, on something of a whim, to buy a kiln. “I thought about doing pottery, but I wasn’t wholeheartedly into it. Then I saw a picture of glass art and it really struck a chord. So, I just got on with it.”

The core of the process is ground glass (coarse, medium, fine and powder) – that’s what fills the colourful jars lining the wall of his studio. Paul first chooses a design and then makes a series of moulds to create a so-called “refactory” of plaster and silica that can tolerate the high temperatures in the kiln. This is then filled with paste, to stop the glass sinking to the bottom, and the layers are built up and overlaid with talc. “After that you put it in the kiln, and then it’s fingers crossed,” says Paul. The process takes about 24 hours from start to finish.

Paul’s studio is lined with jars filled with ground glass.

Inspiration comes from anywhere and everywhere – “I love Celtic designs,” he says, “and capturing the waves and the dolphins that we see here around Lamlash.” But one thing he insists on, “because the raw material is so expensive”, is that nothing goes to waste. He’s become good at knowing his limits, and he enjoys the challenge of working out how to fix a problem. “Because I’m self-taught, I’ve never had someone telling me to do it this way or that way. I do it my way. And if it goes wrong, fine, but I’ve learnt something,” he says.

Paul’s husky Red is “the worst guard dog in the world”!

PAPER

Karebell Studio is the first house on the right along the cart track to Kingscross before you reach Whiting Bay, 10 minutes drive south from Paul’s studio in Lamlash. Owner Karen, a paper cutter, greets me, and as I gush about her beautiful surroundings tells me that “the other day I was coming home and I saw a pheasant, and right in front of it a hare”. Let me briefly set the scene: Karen, standing outside her studio, is surrounded by trees and foliage, beyond which open meadows of cow parsley and grazing cattle. “I wish I’d had my camera with me – it would have made a brilliant photo,” she says.

Karen’s nature photos, many taken near her studio, close to Kingscross Viking Fort, are often the starting point for her cut paper templates. The results line the walls: miniature pieces of finely dissected paper assembled into intricate scenes of Scottish wildlife, Arran landscapes, and whimsical worlds of fairies, mermaids and Mother Nature that tantalises with their twists and tangles and swirls – a kaleidoscope in paper. “It’s like my version of Victorian silhouettes,” explains Karen.

The very first papercut she created was a hare, its alert eyes inspecting the onlooker. It was an anniversary gift for her husband and was the result of Karen looking for “something completely different” to make. After an arts degree and a career in newspaper design – “using my hands and doing it properly, the proper way” – she developed her own papercutting technique when returning to work after maternity leave, she found that digital processes had replaced her job. The hare was based on a technique she saw in a magazine, but Karen’s designs have since developed to become complex and multi-layered.

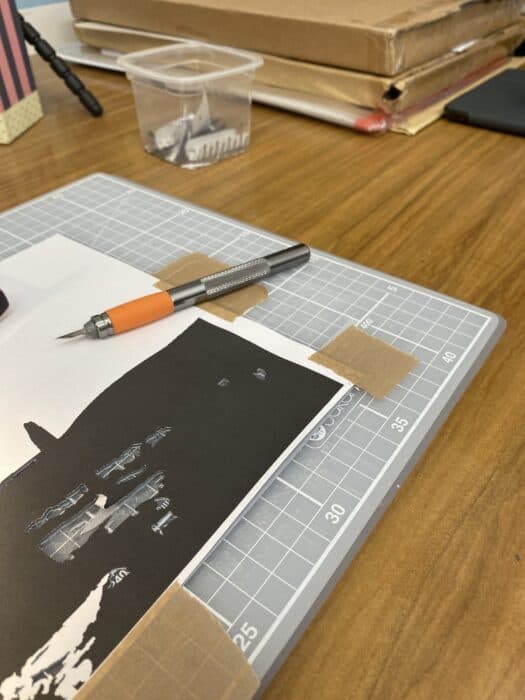

It’s work that requires a “really good knife”. Karen’s favourite is a scalpel-like thing with a soft grip and a short blade. She says she “gets through hundreds”: once the blade goes blunt, it catches on the paper and must be replaced. It must take a lot of patience, I suggest. “Yes, lots of patience,” admits Karen, who might spend up to two weeks creating one piece. “But I always say, I don’t have the patience for knitting, but I have the patience for this.” You also need a steady hand, she says. Lucky for Karen, she loves working with her hands.

When I visit, she is working on a complex design of the Machrie Moor standing stones – it has all the detail of a photo, but the highlights are created by up to 12 layers of tiny pieces of Italian paper with a soft sheen. Once Karen has cut the paper, she will switch on a Harry Potter audio book and set to work to “find a home for all the little pieces”. She says, “I’m doing layer four now, and I’ve just got to build it up, working out what needs to be dark and light. I keep going until it’s perfect.”

Karen is currently working on a design of the Machrie Moor standing stones

Click on the link below to hear Karen describe the process of paper cutting

With Karen’s design in my mind, I’m now heading west, towards the real life Machrie Moor…

WOOD

John Devine in his studio

“There’s an east wind blowing today,” says furniture restorer John Divine, shutting the door to his studio in a barn that must see some weather. It sits between the iconic locations of Machrie Moor and King’s Cave and looks out onto the incisor-like mountains of North Arran. Inside, I take in the full extent of the surrounds, a palette of browns in layer upon layer of wood in various guises. My eye lands on an exquisite Georgian-style Victorian doll’s house waiting to be restored; then a worktable strewn with tools, oils and polishes; a saw sitting in dunes of dust; and arranged here and there, the most marvellous chairs and drinks cabinets, each fashioned from a whisky barrel.

“John Divine – Furniture Repair & Restoration, Cabinetmaker” developed his iconic design during the lockdown. After uprooting his Edinburgh-based furniture restoration and Windsor chair business to Arran in 2010 (and seeing that it would take some time to establish), he took a part-time job at Lochranza Distillery, tour guiding and later distilling.

“In lockdown, when I was furloughed, I discovered a couple of whisky barrels at home, and it seemed a waste,” he says. It is American white oak, he tells me, “very good quality timber”, yet most of the used barrels are broken down and burned – especially in the winter. He dismantled his barrels into the lid, base and individual staves (it’s usually around 50 per barrel) and noticed that the curved shape suited a lot of nice designs – tea light holders, for example, and porridge spurtles. “You can work with the shape,” says John, pointing out the soft curves in every clock and stand. “It’s endless. The only limit is your imagination really.” Arranach Barrel Furniture was born, and his portfolio now encompasses benches, chairs and a very popular drinks cabinet.

John uses Medieval-style bolts

The distillery loved his work from the off and became an early customer, and when I meet him, he is working on a big order for the recently opened Lagg Distillery. He also takes commissions, but all his designs have one thing in common: they are made uniquely from wood that has been in contact with Lochranza whisky – sherry casks, bourbon casks, and standard American oak. He invites me to take a seat in a chair, a beautiful Windsor-style thing with Medieval-like studs. I settle back, enjoying the support it gives my spine. “They’re very comfortable,” confirms John. “They don’t look it, but they are – everyone says so.”

John explains the process of preparing staves

A chair like this might take him a week to make. There are challenges, like sourcing the sherry cask tops he uses for the seats, but the most time-intensive process is cleaning the staves – removing the char in a five-step process and finally sanding it down. “It’s a very dirty process – you get covered in stuff. This is clean!” laughs John, pointing to his dust-speckled apron.

Barrel staves at various stages of cleaning

Besides remodelling barrels, John works with his neighbour, the joiner Andy Leese (another Arran Open Studios participant), adding wax and polish or upholstery to Andy’s furniture. But his next big job is restoring the magnificent doll’s house that caught my eye upon entering his workshop. “All I’ve got to do is try and redo all the different trims and make it look nice again,” he says, as if he were going to simply repaint a garden fence.

About Arran Open Studios

Arran Open Studios is an annual initiative incorporating painters, sculptors and craftspeople from the Isle of Arran. Launched in 2012, it operates under the umbrella arts charity the Arran Theatre and Arts Trust. This year, it takes place from 11-14 August.