With three months to go until Arran Open Studios 2023, Arran-based writer Emily Rose Mawson visits three participating studios that explore the natural world in very different mediums.

Rob Stevens of Gobhlach Studio

Clay

“This is pure Isle of Arran clay, made and fired here,” says mixed media artist and Arran Open Studios participant Rob Stevens as he hands me a fist-pommeled ball the colour of burnt terracotta, the same shade as many of the island’s paths. The clay feels coarse and rough under my fingertips. He then hands me a bear sculpture, much smoother, also made from Arran clay. “You have to know how to blend it”, Rob explains.

To work with the material on a potter’s wheel – his, a traditional model acquired from the Arran potter Hugh Purdie – he mixes it with refined clay. This is in keeping with his whole artistic process, which he treats as “a laboratory of ideas”, combining “rawness and a connection with nature” with “material from the actual landscape”.

Rob treats his workshop as a “laboratory of ideas”

The landscape: for Rob, who established Gobhlach Studio in Pirnmill on Arran’s west coast, the immediate landscape stretches along the banks of the burn of the same name, from his garden of bright tangled flowers to billowing oak, birch and hazel trees that climb upwards into the hills. He moved here with his wife Jane five years ago after retiring from his position as head of fine art at the Royal Grammar School in High Wycombe, and has since dedicated himself to mixed media experimentation, with a focus on ceramics.

Visitors to Gobhlach, which also features on the Arran Art Trail, will see 2D work, which reflects elemental forms in the 3D work, such as spherical sculptures of Arran’s 500-million-year-old Imachar rocks – “I like that they are hinting at things that are beyond human conception in terms of time,” says Rob. There are paintings and cast ceramics, and cute sinewy creatures atop driftwood. “These? These you only find in Pirnmill,” says Rob with a glint in his eye. “They’re a cross between a seal and an otter – I called them a slotter!”

‘Slotters’ are unique to Pirnmill

Rob studied ceramics and three-dimensional design at Wolverhampton in the 1970s, then spent five years volunteering in Sierra Leone. Here, he developed pottery and brickmaking, and the simple raw materials and technologies used have “influenced me a lot ever since,” he says. His other big influence, especially since moving to Arran, is nature. He works in outbuildings burrowed into the grasshopper green of the burn’s banks, where he explores the laws of growth, “the mathematics and geometry in how trees grow or rivers fork”, seeking inspiration in what these patterns reveal about underlying forces. “I want to reuse some of those forces – gravity, compression, patterns – in my art,” he says.

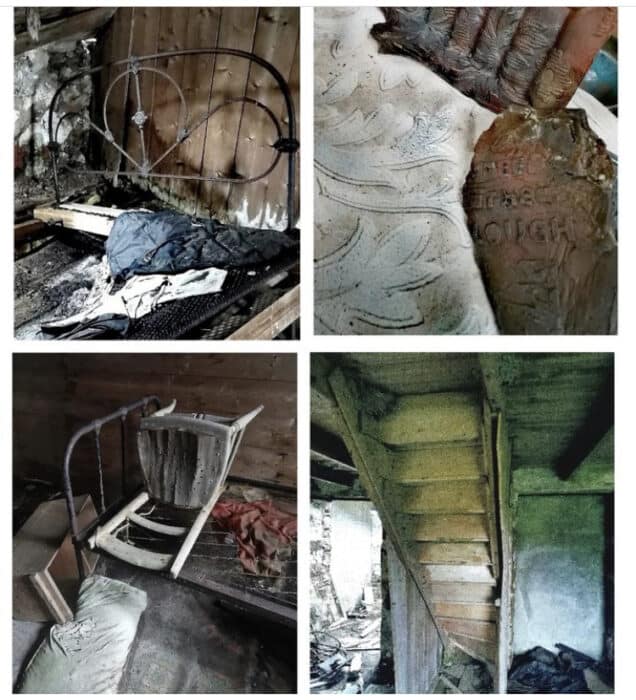

His current experiments – including an abundance of sketches and a clay model of a staircase – are for a project in September with an international textiles artist, on abandoned local crofts. “I don’t know how the sculptures will come out, but they’re based on the idea of the past. I’m looking at a derelict croft and I’m thinking how I might use clay to capture a memory of the place,” he says. One technique he has tried is adding metal powders to the clay to make it look wizened – “to hint at a life”.

Some work based on a project on abandoned local crofts

Next Venture for Rob

Rob setting up his kiln for a Raku firing

Wheat

The other galleries I planned to visit today are in the Whiting Bay area, on Arran’s east coast, and so it is that an hour later, after an Arran Ice Cream (Pirnmill Stores next door to Gobhlach has a good selection) and a beach stroll in front of Rob’s studio, I find myself halfway up the lane to Auchencairn, in a sea-view timber-clad studio tucked beyond hedgerows embroidered with wildflowers, where Julia Bovee is weaving wheat. The scent is one of sweet, dried grass, and piled on the floor are mounds of golden wheat sheaves.

Julia, otherwise known as the Wheat Weaver of Auchencairn, recently collected a van full from Staffordshire. She will now spend a couple of weeks stripping the sheaves, “then I’ll bag it up, to keep away pests, and grade it into small, medium and large stems,” she explains. The wheat is then soaked in water for an hour to rehydrate it and make it workable, but “you only get about 24 hours before it dries out, so you have to work quite quickly,” says Julia.

Julia recently collected a van full of wheat sheaves from Staffordshire

Inspired by folklore – she used to go to the Carshalton Straw Jack in Surrey every year – Julia, whose background includes glass- and metalwork and costume design, took up wheat weaving after moving to Arran. She was invited to join the Druids of Arran ceremony and wanted to make something sustainable to take. So, she ordered some wheat and started teaching herself, and the rest, as they say, is history.

A wheat weaver’s tools

These days, her creations put the couture into corn dollies: there are Arran maidens with lioness-like manes; woven wheat-head collars; and a crown of leaves and wheat horns. Beside the windowsill, a noticeboard displays cuttings of fantastical Alexander McQueen corn gowns – a reminder of the influence this humble material has in the business of high fashion. Julia herself likes her mother nature figures best. “And contemporary pieces. At the moment, I’m working on more sculptural pieces,” she says, playfully donning the crown.

Julia wearing her woven crown

Julia’s take on corn dollies

She also teaches basic technique courses, and during Arran Open Studios, visitors can have a go. Last year a milliner from Spain visited because she wanted to learn how to make plaits to incorporate into her hats, but you don’t need any experience to have a go and “most people get it”, says Julia. She is sitting at the window working five stems, and as her fingers manipulate the wheat – one over two, one over two – I’m transfixed; I feel I’m watching dancers around a maypole. Within minutes she has created a woven orb, which she hands to me as a memento.

She tells me her work is becoming more specific to Arran, “in what I find and what I use”, and I wonder if Arran, somewhere that still grows wheat, has a history of wheat weaving. “Back in the day, people would have woven buttonholes – for example, gentlemen would have woven little favours for their sweetheart,” she says. But she has been unable to find anything specific to Arran. “Come on Arran, show me your corn dollies!” she jests.

Julia demonstrates her craft

Cotton

My final stop of the day is nearby, in central Whiting Bay. Tucked just above the main street, also surrounded by a dazzling garden with sea views, is creative stitcher Jan MacGregor’s studio. Inside, the first thing I notice is colour. There are bright pictures all over – of pastoral landscapes, of shoals of fish, of Whiting Bay itself. “Every other picture you can see in this house is by my late husband, Ken,” says Jan, as I follow her to the studio, my eye continuously drawn to a different piece of art.

“Ken was an artist when he retired, and he’s really how I got into it,” she explains. “While he was still working (as a community worker), he went to art school at night. At my first Open Studios, I only sold his work – I had a lot of his pictures.” Jan retired a few years before Ken died and with more free time, decided to try producing something herself. “I attended an Arran Visual Arts workshop on Creative Stitching with Laura Lees, and that set me sewing.”

Jan with one of her very first creations

Her work is a delight – landscapes captured in fragments of scrap textiles. It is conceived in the studio, a light-filled space with a sewing machine in one corner. There’s a collage clamped under its foot: Jan’s latest piece, depicting Whiting Bay. “I use anything I can get my hands on. I keep tiny bits of material that I might use for something,” she explains. She then selects the background fabric, and paints it with silk paints, before adding different cuttings – frayed edges and all – with applique stitch. A piece like this might take Jan two to three working days to finish, but she spends a lot of time planning – all in her head – and finding the right pieces of fabric.

Jan starts to stitch her piece ‘Whiting Bay’

When I meet her, she is busy preparing work for an upcoming Arran Visual Arts exhibition. She is now the chair of the organization that launched her into the world of art. It was set up by her husband in 2001 to develop the arts across the island and one of its projects is the weekly Art in Mind group, held at Arran Ranger Centre. “It’s a magical group,” says Jan. “People feel safe, and if they want to talk about problems, there’s always someone who will listen. But lots of people come and just focus on their art, and if they’re having a bad day, they almost always go home feeling a bit better.”

Community is an important part of Jan’s work. When she opens her doors for Arran Open Studios, it is as ‘Jan and friends’, inviting other artists to use her space to exhibit and sell their work. This year it will be David Samuels, who designs custom-made furniture, shaker chairs and taiko drums, and the wood turner Ruth Mae. “Ruth creates the most beautiful bowls that look as if they’re made of porcelain, but they’re actually made of windblown timber from Arran,” says Jan.

With daylight hours to spare, I take my leave of Jan and set off to walk Whiting Bay’s iconic Glenashdale Falls circuit into the evening. I see wild garlic and rosebay willowherb and daisies and bluebells, and the scene is just like Jan’s textile creations: a marvellous chaos of colour and texture.

About Arran Open Studios

Arran Open Studios is an annual initiative incorporating painters, sculptors and craftspeople from the Isle of Arran. Launched in 2012, it operates under the umbrella arts charity the Arran Theatre and Arts Trust. This year, it takes place from 11-14 August.