Arran Open Studios: Made of nature

Arran is known as “the Arts Island”, with talented artists and craftspeople at work in every nook and crannie. Two weeks before they welcome visitors for Arran Open Studios 2023, our writer Emily Rose Mawson heads to the east coast villages of Lamlash and Brodick to catch up with four of the participants.

Stone and oil

When Tim Pomeroy and Josephine Broekhuizen moved to Arran from Aberdeen 25 years ago, it was inspired by a need to escape the frenetic white noise of an urban setting and focus more deeply on their art. “It’s a search for that sophistication, that deeper thing,” muses Tim, the world-renowned sculptor, who sees his art as a quest to connect with deep time – “what it is, what it means to be an evolved human”. Arran’s ancient landscapes are the ideal setting, then? “But you find inspiration anywhere, you can’t help it,” inserts his wife Josephine, who grew up in The Hague, went to art school in Rotterdam, and was one of the founding members of Arran Open Studios. Her enchanting oil paintings and screen prints are largely inspired by her exquisite coastal cottage garden.

We’re sipping morning coffee in the kitchen of their turn-of-the-last century farmhouse and smallholding just south of Lamlash, where Arran faces Holy Isle. The couple’s shiny black pug Mabel is clambering across Tim’s lap and their cat, who “dislocated her hip last week in a fight”, is prowling the table hoping for one of the freshly baked pastries. “We grind coffee every morning by hand. It’s part of the experience of having the coffee. People have an inherent need to make with their hands,” says Tim.

Tim and Josephine with their black pug Mabel

He’s currently exploring gold in his work. But it’s not about creating a commodity. “It’s a matter of, what else can you leave out in the open air for 4,000 years that doesn’t change in that time?”. And it’s the same with stone, he continues. “If you put my sculptures into the ground, they’re going to come out largely as they went in. I like, in fact I would champion, the concept of permanence.” It’s “ephemeral art”, inserts Josephine.

Theirs is an adoring repartee of back-and-forth musings arisen from a life of shared art. The pair met at art school in Aberdeen and now share a studio space that is separated into an area for sculpting and an area for painting. All around, Josephine’s garden meanders in a mosaic of plants – species like Hostas, New Zealand Flax, Bergenia, Lychnis Chalcedonia and Dahlia – towards their woodland and down to the sea. She is “a seriously good gardener”, says Tim, but she carves out time every day to paint – captivating still lifes, landscapes and figurative paintings – and recently took a screen printing course with Glasgow Print Workshop. “The material does something that inspires you. It’s a two-way thing,” she says.

It’s the same for Tim. As a sculptor, he explains, there’s a reciprocal arrangement between working a piece of stone and being worked by the piece of stone. “As you’re hitting into the stone, the stone is hitting back. Not literally, but the same percussion,” he says. Josephine interjects: “And it creates so much dust. Dust for Scotland.” Tim agrees. He’s working on a limestone commission, and says it sticks to everything. “But it’s beautiful to work with,” he continues. “It releases the methane from the sea creatures laid down millions of years ago, so as you carve into it you are bathed in a kind of fug of methane. I find that connects me with the past.”

During Arran Open Studios, visitors receive a map of the garden and woodland, where there is a sculpture trail. “It started with a mistake – I couldn’t use the sculpture or look at it, and one day I dragged it down here with my tractor and dumped it, hoping that grass would grow around it. But as I walked away, the light caught it just so, and… well, here it is,” explains Tim. In another corner there is a wave sculpture that was originally created for a private yacht.

There is a sculpture trail in the woods

As we walk the garden, Tim points out a sculpture topped with gold leaf. It’s cloaked in pink campion and looks exquisite. “You need to feel that the universe is the most permanent thing we know,” reflects Tim. Josephine smiles, leaning in to take a closer look at the flowers. And they walk on, hand in hand, between the foliage and the sculptures.

A corner of the artistic duo’s rambling grounds

Black clay and porcelain

Kirsteen in her studio

“I love ceramics…” says Kirsteen Holuj. “… Even though it can be, it is, the most frustrating, time-consuming, expensive subject.” She thinks for a moment. “I guess I love its versatility…? It can be whatever, as long as you’ve got the patience to work it out, and to go through the making and the firing and the cracking and the drying and the glazing and the exploding.” It’s best in its wet form, she says. “After that my love for it depreciates until it’s finished.”

When we meet, the potter is eking out space for her studio in the garage of the Brodick home she and her husband bought less than a year ago. Kirsteen grew up in Scotland and after years in London and Buckinghamshire, wanted to move back – for the lochs, for the mountains, for the forests. Her section of the garage, which has a view straight across the bay to Brodick Castle, is a potter’s paradise: a potter’s wheel encircled by mark-making tools, ribs, scrapers and grouting tools. “And, you know, a sponge on a stick, to get water out from the inside,” she says. In the corner there’s a kiln, beside it a floral upholstered chair “that is deliberately very uncomfortable”, and all around, arrangements of Kirsteen’s striking monochrome pots.

Her technique is rather unusual. “I work with black clay, which is really messy, and I work with porcelain, which is pure white,” she explains. She will throw a cylinder, dry it, and then “paint on nice thick, gloopy porcelain, before scoring the surface with a comb tool”. What makes the process even more skillful is that while you’re throwing the pot on the wheel, you can only touch it from the inside. “You’ve just got to use your sense of touch,” says Kirsteen.

Kirsteen works with black clay and porcelain

She describes her work as landscape inspired. “I’m not sure whether my technique or seeing the landscape comes first. Sometimes you really like the way something turns out, and it looks like a field with a dusting of fresh snow,” she says. Her black-and-white scored pots are called “Winter Field”. There’s another series named “Light on water” and then “Winter Sky”. She shows me a smooth, spherical pot with steely swirls and says: “You’ve seen skies like this here – especially down at the south end of the island.”

It’s the making she enjoys the most. As a child, she liked “knitting, sewing, anything makey”. She qualified in interior design, but discovered pottery during an evening class when her children were little. She went on to acquire a studio at Westbury Art Centre in Milton Keynes, and for 20 years taught pottery at Milton Keynes Art Centre while producing her own work.

As well as black clay and porcelain, she now works with glazing (for her blue-coloured pots) and Raku (a type of low-fire pottery). Lately she has been experimenting with metalwork to add lids to the pots – the result of a course she took after lockdown because “jewellery, well, it’s so instant”. One of her fondest memories is helping rebuild a soda kiln while at Westbury. “I love the texture, I love that the soda gives this kind of orange peel effect,” she says. It’s why she’s hankering after a fired kiln. “The trouble with an electric kiln is that you know what is going to come out of it. With firing, you never know,” she says. “And porcelain in a soda kiln does really exciting things!”

Silver

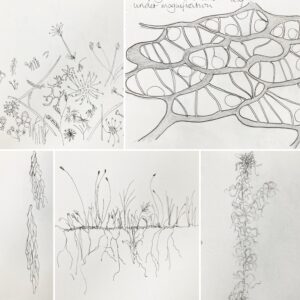

The first thing you notice as you approach Ann Hume’s garden studio is her exquisite array of flowers. I’m admiring them when she tells me that it’s a constant battle with nature, slugs, pigeons, aphids and the weather – all challenges that the Brodick-based jeweller is addressing with an eye to ecology. Her silver work grows out of nature, and a recent project inspired by peatlands firmed her resolve to, among others, switch to peat-free compost. Opening a sketchbook, Ann shows me “doodles” of the sphagnum moss that thrives in peatlands – intricate drawings in black ink of twisty, curly patterns. They were made during a visit to Arran’s Maol Donn peatlands near Corrie, where National Trust’s Arran Ranger Service is restoring depleted peatland.

Ann’s sketchbook drawings

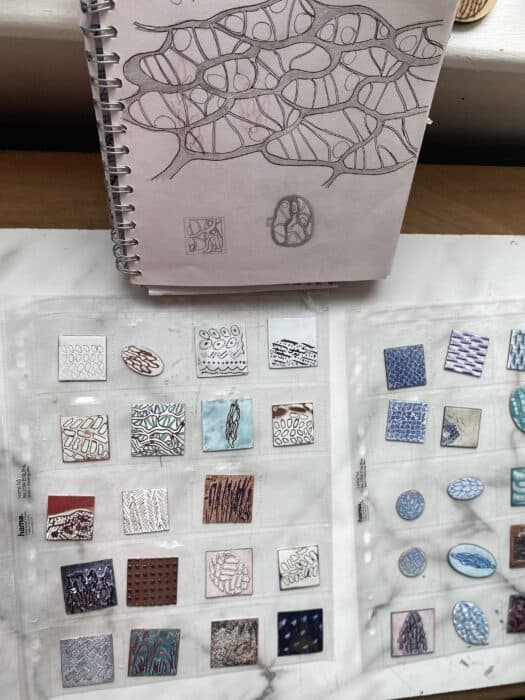

Ann’s latest project is inspired by sphagnum moss which thrives in peatlands. Ann’s drawing of a sphagnum leaf through the microscope along with various enamelled samples she has created as part of her project.

The first three finished pieces were exhibited during the Arran Open Studios preview exhibition in July. They’re a journey into “creative expression”, says Ann. But her commercial jewellery is also inspired by natural forms. “The petal work – from looking at flowers,” she explains, showing me delicate silver folds suspended on a fine hoop pendant. Or seed pods replicated in pebbled designs, and pieces inspired by the microscopic sea life known as diatoms.

There is seaweed too, their fronds captured in silver, but Ann also interprets nature with textures on the surface of her jewellery – often created via various enamel techniques. “If you slightly over-enamel, you get other colours coming through – see the blue, and the olive here,” she says, showing me a delicate pair of seaweed-inspired earrings. Or you can draw into the enamel with nibs, “like sgraffito”, and even use enamel as a resist to leave a dotted effect. Some of her designs start with a 3D print design created by Arran Makerspace, that are then “cast, cleaned up, and enamelled”.

Silver as a material “just takes practice,” she says. “The finish is the most difficult thing, using files and finer and finer grades of emery paper. I use templates to get shapes, then saw them out. And I use a doming block and doming punches, and hammer it if I want to create curves,” she explains of her process. “You have to heat the silver first, to make it more malleable. As you work with it, it becomes ‘work-hard’ and you have to heat and cool again. You can do that many times in the process.”

She works out of her father’s old chair – a wizened burgundy leather thing. “He was a barber. I used to swing around on it when I was a child. There must have been so many stories told in this barber’s chair by men in the 1950s, getting their short back and sides,” she smiles. Her jewellery bench, a beautiful creation in oak, was made by a friend’s Dad. When she was a child, in Glasgow, her workbench was a “big camp table”. I used to spend all the time in my bedroom, drawing and painting,” she says.

Ann works from her father’s barber’s chair

She went on to study drawing and painting at Glasgow School of Art, and after graduating worked in various jobs until she became a primary school teacher. Twenty-four years of teaching later, she finally committing to her own creative work when she and her husband, who is from Arran, moved back to the island 13 years ago. “I started jewellery 18 years ago after going to an evening class with a friend, and I really liked it,” she says. “Once we were settled on Arran, I set up a workshop in my house and six years ago opened this studio.”

Her Arran art journey also included working with the artist Angela Elliott-Walker to set the Arran Art Trail (it’s now run by Heather MacLeod and Lynn Jones). “This brought visitors to my workshop, and it’s all been really, really great. After years of teaching and bringing up my children it’s been good to focus on my own creative work.”

About Arran Open Studios

Arran Open Studios is an annual initiative incorporating painters, sculptors and craftspeople from the Isle of Arran. Launched in 2012, it operates under the umbrella arts charity the Arran Theatre and Arts Trust. This year, it takes place from 11-14 August.